Building a Defensible Cyberspace

The 2017 New York Cyber Task Force Report

Building a Defensible Cyberspace

On September 28, 2017, the New York Cyber Task Force released a series of recommendations that would help make it easier to defend cyberspace without sacrificing the utility, flexibility, and convenience that has made the Internet so essential to our economies and personal lives.

In its report, entitled “Building a Defensible Cyberspace,” the task force highlights strategies for government, cybersecurity companies, and other IT-dependent organizations.

Among other things the report finds that:

- It is possible to establish a more defensible cyberspace—an Internet where defenders have the advantage over attackers.

- Defending cyberspace will not require a “Cyber Manhattan Project.” Security professionals have developed effective strategies in the past, and with the right kind of innovations defenders will once again enjoy the advantage.

- Improvements may come from unexpected places and rely on unglamorous strategies.

- The best options use leverage—innovations across technology, operational, and policy that grant the greatest advantage to the defender over attackers at the least cost and greatest scale.

The New York Cyber Task Force included about 30 senior-level experts from New York City and elsewhere, counting among its members executives in finance and cybersecurity, former government officials, and leading academics. The group’s co-chairs are Phil Venables of Goldman Sachs, Greg Rattray of JP Morgan Chase, and Merit E. Janow, the dean of Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, which organized the task force.

Other contributors included Katheryn Rosen of the Atlantic Council, Neal Pollard of PwC, Dmitri Alperovitch of Crowdstrike, Melody Hildebrandt of 21st Century Fox, David Lashway of Baker McKenzie, Elena Kvochko of Barclays, John Carlson of the FS-ISAC, Ed Amoroso of TAG Global (and former CSO of AT&T), and Columbia University scholars Steven M. Bellovin, Arthur M. Langer, and Matthew Waxman.

Report Excerpts

Cyberspace—the Internet and billions of devices connected to it—must be made more defensible, at scale and at modest cost, or it will cease to drive economic, social, and cultural empowerment as it has over recent decades.

Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs convened a New York Cyber Task Force (NYCTF) to assess how we can achieve a more defensible cyberspace and to develop recommendations relating to technological, operational, and policy innovations necessary to achieve that end. Task force members discussed the most defensible past innovations, the keys to their success, and the innovations policymakers, technologists, and cyber defenders should pursue next. The way ahead is hard, but a defensible cyberspace is possible.

Keeping cyber attackers from gaining a foothold in computers—and kicking them out once they do—remains easy to imagine but difficult to accomplish in practice. Why has this been so challenging? Every cyber defender has their own favorite reason. The NYCTF identified the following as some of the most important:

- Insecure internet architecture caused by specific design choices: “The Internet is not insecure because it is buggy, but because of specific design decisions” to make it more open, explains pioneer computer scientist David Clark.

- Marketplace forces encouraging low-quality software: Not only is it impossible to write bug-free code, but “[t]here are no real consequences for having bad security or having low-quality software … Even worse, the marketplace often rewards low quality,” according to security expert Bruce Schneier.

- Security strategy that targets symptoms rather than underlying issues: Fixes typically target symptoms rather than underlying problems. To paraphrase Phil Venables, NYCTF co-chair, the uninterrupted production of insecure IT products forces companies to buy ever more IT security products

- Attackers emboldened by differing national laws and ease of evading authorities across borders: Cyber crimes, warfare, and espionage can seem risk free because of the often difficult process of attribution, ease of crossing borders to stymie law enforcement, sanctuary certain nations offer cyber criminals, and differing national laws

- Increased security often inhibits ease of use and convenience: Improved security often imposes costs on ease of use. As a result, it is frequently bypassed, or never even implemented by individual users and beleaguered IT staff

- Lack of in-depth knowledge among consumers leads to difficulty in choosing effective products: “Most consumers have no real-world understanding of [cybersecurity] and cannot choose products wisely or make sound decisions about how to use them.” This is as true today as when it was written in the 1991 Computers at Risk report. Cybersecurity has gotten so complex that even IT staff struggle to understand the products.

- Human error cannot be programmed away: People can be tricked or grow disgruntled and, in the words of one expert, “are always the weakest link … you can deploy all the technology you want, but people simply cannot be programmed and can’t be anticipated.”

- Growing complexity of attacks necessitates increased costs for security: Defending this attack surface has required a profusion of new tools. “Increasing complexity increases cost” and “decreases the predictability of new costs.”

- Disparate reporting and lack of an overarching defense strategy: Few, if any, of the various reports or cyber strategies lay out an overall approach to bind the work or guide between competing priorities. They are instead lists of critical tasks with no underlying theory of how these tasks will lead to success

The NYCTF has focused on the question, “Which innovations—across technology, operations, and policy—have made us the most secure at the least cost?” Rather than simply listing important next actions, cyber strategists should assess innovations and prioritize those that improve defense on the greatest scale and at the least cost, based on the precedent of successful past innovations.

Not all defense innovations have been equally important. Those with the highest impact have created leverage. To make a real difference, an innovation should have two key traits:

- Defense advantage: Any innovation by defenders must impose far greater costs on attackers. A “dollar of defense” (or hour or other measure of input) should not yield just a “dollar of attack,” but should force attackers to spend considerably more to defeat it.

- Hyperscale: The innovation must easily, even automatically, work across enterprises or cyberspace as a whole.

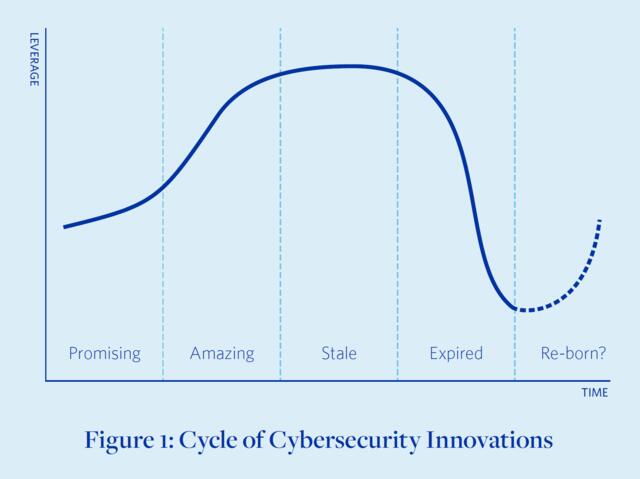

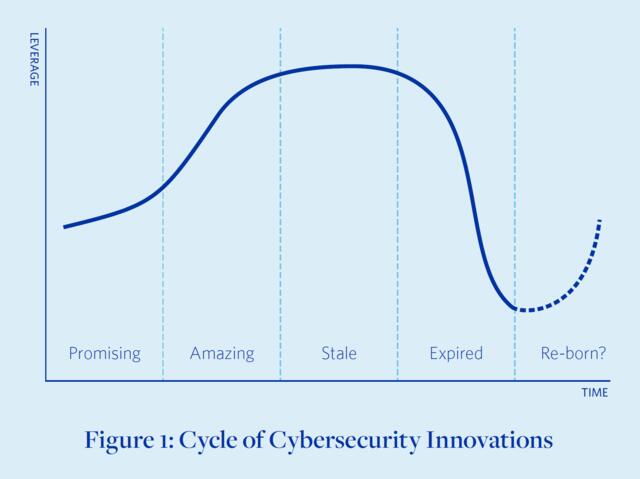

Even the best innovations have an expiration date. They roll through a cycle of four stages: promising, amazing, stale, and expired. They fade as technologies change, adversaries adapt, and complexity increases.

Static and prescriptive “checking-the-box” cybersecurity typically also creates negative leverage. While perhaps satisfying regulators, these protections often force defenders to expend far more effort than it costs attackers to circumvent them. This was not always the case. Two decades ago, cybersecurity architectures were less complex and threats less varied, so defenses built on static checklists were more effective at keeping out adversaries. Check-the-box compliance has, in short, gone from essential to albatross. Once a game changer, it has over time become a drain on the resources of defenders.

Most expired innovations should be retired, or at least de-emphasized. But some might gain a new lease on life if it is possible to drastically reduce their costs, use them in combination with other innovations to extend their life, or otherwise revamp them to regain leverage.

The NYCTF has determined that to become more defensible, cyberspace must be:

- Tolerant of flaws, strong and effective under adversity

- Capable of agile decision making and crisis response

- Well managed by multiple stakeholders • Capable of constraining negative externalities

- Capable of swift and well-coordinated responses

- Instrumented and measurable

- Viable and valuable over the long term

The NYCTF posits that cyberspace can be made defensible by applying innovations with leverage, including technological, operational and policy innovations. In Building a Defensible Cyberspace, the Task Force provides the following recommendations:

| For the US Government | For IT and Security Companies | For IT-Dependent Organizations |

|

|

|

The report also addresses which factors distinguish those innovations that create leverage from those that do not.

Lesson #1: Game-changing innovations share one key feature: scale massively aids the defense. The massive scale of the Internet usually aids attackers. Ever more devices and increasingly complex software means more doors potentially left unlocked. The most successful cybersecurity innovations reverse this dynamic and employ scale to advantage the defense. They are far easier for defenders to deploy en masse than for attackers to circumvent.

Lesson #2: Game-changing innovations use the minimum necessary intervention. One particularly low-intervention strategy is to increase transparency, enabling more informed risk management. The simplest transparency comes from media coverage. In a 2015 poll of CISOs, a majority “cited news coverage of large and harmful security breaches as the driver for increased budgets”; such coverage provides policymakers plenty of teachable moments to push important programs.

One of the better examples of transparency relates not to technology, but to national policy. The best solutions are often based on the ways society and organizations have tackled similar problems. The US Securities and Exchange Commission has advised the boards of directors of publicly traded companies to disclose “material” cyber incidents to investors, as they would any other risk. There is still far to go (such as deciding what constitutes materiality), but with just 2500 words piggybacked onto existing private-sector governance mechanisms, the SEC is encouraging boards to focus on cyber risk.

Lesson #3: Operational and policy innovations are powerful but overlooked and misunderstood. Cyberspace is a technical domain, and the vast majority of experts are techies: software or hardware developers, network engineers, or security researchers. A computer “expert is seldom an expert on consequences and policy implications,” as one author put it in 1965. Policymakers, with their nearly opposite skillset and body of knowledge, rarely understand the technology and can underestimate second- and third-order effects as well as the effort needed to successfully implement policies.

Not all coming innovation will provide leverage to defenders. Quantum computing, for example, will almost certainly provide more leverage to attackers by rendering most modern, non-quantum encryption worthless. Other coming innovations will help both defenders and attackers; it’s still too soon to know who will gain the most. Blockchain and other distributed ledgers have significantly helped attackers, who use hard-to-trace bitcoins as payment for cybercrime services or as part of a payment demand to unscramble data in ransomware attacks.

A collection of technologies related to automation and autonomy are among the greatest hopes for defensible breakthroughs. Artificial intelligence might soon be able to stop hackers faster than any human defender

Political, cybersecurity, and thought leaders must set a strategic goal of creating a defensible cyberspace, where the defense, not the attackers, have the advantage. A more defense-advantage Internet is possible.

Of course, a myriad of incremental solutions will always be required. In the early decades of computer security, such solutions were far cheaper than more fundamental fixes. The accumulated weight of layer after layer of incremental band-aid solutions has now become so significant (annual cybersecurity spending is projected to reach $170 billion by 2020) that more wide-scale fixes are needed.

To achieve more significant results, defenders must recognize and emulate the innovations with the greatest leverage.

It is difficult to pick the true winners in advance, but several across technology, operations and policy stood out in our conversations within the task force and with other experts. There are still potentially large, relatively easy, leverage-creating gains to be had. Because of the sometimes tight linkage between the innovations of policy and of operations, these are categorized together.

Technology-Focused Innovations: There are major gains still to be made with cloudbased technologies. Cloud-based technologies offer the chance to build more secure architectures without pouring investment into an increasingly indefensible perimeter. With the cloud, defenders can use scale to reduce complexity to more tractable levels: if everything resides on cloud, then there is only one set to keep updated and secure rather than dozens, hundreds, or thousands. Further, with sufficient data and computing power, the cloud enables revolutionary new ways of analysis, measuring, and monitoring.

Operational- and Policy-Focused Innovations: Faster patching is one of the most critical ways enterprises can protect themselves. Software that automatically updates itself is of no use if the process is delayed by enterprise IT staff that needs to exhaustively test every new change. The WannaCry attack of May 2017 would have been stopped in its tracks if only enterprises had applied the existing Microsoft patch. Yet on average organizations take 12 weeks to patch, far longer than hackers need to turn vulnerabilities into exploits. Much of that software remains unpatched because it is so out of date. There are still perhaps 140 million computers running Windows XP, even though it became officially obsolete and unsupported in 2014. Accordingly, updating obsolete software is a critical “innovation” that provides significant leverage.

Given the many advantages offense has, these relatively easy gains may be insufficient to make cyberspace truly defensible. At some point, decision makers will have to face harder choices. Certain potentially game-changing solutions require uncomfortable answers to the key question, “who pays?” As such, the members of the task force did not reach a consensus on the following tactics.

More extreme transparency measures, like a “nutrition label” for software, could drive market decisions by providing consumers and IT managers more information about the components and security of competing products. Such a tactic would be difficult to implement. Software is complex, and many vendors would resist, potentially making government regulation, rather than pure market forces, necessary.

Creating a new Internet, although not a favorite option of the task force, not least because of the expense of developing more secure standards and deploying new equipment, is a serious idea with serious backing. Former NSA director General Michael Hayden proposes a more reasonable approach: a two-Internet future. In the first, based on today’s network, security cannot be guaranteed, more is permitted, and anonymity is allowed (and even cherished). The second is far more secure and restrictive and requires disclosure of identity. The former is for fun and free speech, the latter for business and, especially, critical infrastructure.

Determining whether and how to punish nations that are sponsors of or sanctuaries to destabilizing cyber attackers is among the most difficult policy challenges. In Washington, DC, this may seem relatively straightforward in conversations about deterring China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. But it is not that easy, as the US Intelligence Community has also been active in finding dangerous vulnerabilities in software made by US vendors and using them against the systems of other nations. In many cases, those nations have reason to believe the United States threw the first punch, and deterrence works very differently when nations feel they are retaliating rather than striking first. A careful balance must be established between deterrence and restraint.

New York Cyber Task Force Reports

The New York Cyber Task Force has spent the last year investigating the private sector’s perspective on the current and future state of operational collaboration, as well as to understand the federal government’s aims and aspirations in improving how industry and government work together.

The New York Cyber Task Force gathered to address how the US government and private sector can enhance cyber readiness through operational collaboration to protect the nation.