SIPA Class Analyzes Media Coverage of COVID-19

The COVID-19 crisis has shown once again how essential quality information is to democracy. Without accurate reporting, policy makers and societies can not function. So the 2020 pandemic was an important teachable moment for students in my course on Global Media: Innovation and Economic Development. Under normal circumstances we look at how journalism contributes to democracy and economic development, and we spend a lot of time talking about investigative journalism in the global south, the role of philanthropy, and the niche startups that provide information essential to society.

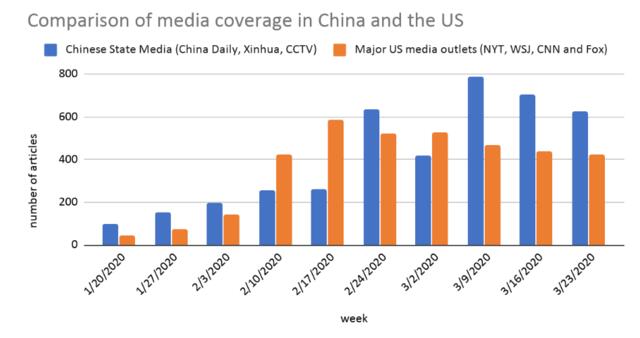

Mis- and disinformation have become a big part of our discussions, so the COVID-19 pandemic gave us an important case study unfolding before our eyes. The class was excited for a chance to work together on an analysis of media coverage of COVID-19 and, since we have students from six countries in the class, we decided to do a comparative analysis of media coverage in order to understand what narratives and frames were being adopted and how they changed over time.

As students scattered across the world, returning to quarantine or isolate themselves in their countries, they continued their research working with Alexandre Gonçalves, a Columbia PhD candidate in journalism, to scrape data from social media channels and from legacy media websites. Gonçalves has been helping in my class for a few years now and he generously rose to the occasion, spending hours making a series of YouTube videos that students could watch at their convenience. Armed with an understanding of how to collect information about news coverage on COVID-19 and the ensuing reaction on social media, they began to analyse trends in Brazil, China, Korea, Singapore, Germany, Vietnam, and different parts of the United States.

As would be expected, each country's media coverage reflected its own preoccupations. The U.S. coverage demonstrated polarization over politics largely along party lines. President Trump’s active support and amplification of protests by right-wing conspiracy theorists who are in the minority contrasts with the majority of Americans who are worried that governors will open up states too quickly.

Asian countries, on the other hand, have tended to stress national unity. Unsurprisingly, state-controlled Chinese media praises the government response to the crisis, and highlights “positive energy” stories, detailing heroism of doctors and nurses, generous donations from various channels, and particularly support and solidarity from foreign countries, organizations and individuals with the Chinese government to win the anti-virus battle. As signs showed progress in containing the spread of the virus, Chinese media highlighted the central leadership and the institutional strength in fighting the unprecedented crisis, while refuting criticism about the government’s quarantine measures and about its transparency in epidemic control.

Many nations have also had considerable coverage of the economic hardships people have been experiencing. In Germany, articles detailing both the state’s support measures for small businesses and the lack of an EU-coordinated economic plan have gained traction online.

Countries that have been more successful in controlling the virus used official media to broadcast their successes. As one Singaporean student noted: “Self-praise or self-confidence, it seems like former Singaporean diplomat Professor Tommy Koh’s call for ‘remain[ing] very Confucian, very humble and modest’ in spite of success has fallen on deaf ears.”

Singapore and Vietnam are two examples. In Singapore, the pro-government Straits Times ran multiple articles in February and March quoting WHO officials’ praise of Singapore’s response, and the Harvard study that considers Singapore’s approach “gold standard.” Among articles lauding Singapore’s COVID-19 response from Time, CNET, and Forbes nestled one penned by Kazakhstan’s ambassador to Singapore, who wrote in The Straits Times how much Kazakhstan has learned from “watching Singapore.”

While Trump’s move to declare himself a “wartime president” during this health pandemic has been met with criticism in the United State., the Vietnamese people have been receptive to their government’s militaristic rhetoric. Indeed, 62 percent of Vietnamese people are content with their government’s response to the Covid crisis, an outlier in a time when many polls are showing lower degrees of trust. Vietnamese news coverage has been marked by a prominent narrative: “Every citizen is a soldier fighting the disease.” A viral propaganda poster by artist Hiep Le Duc reads “To stay home is to love your country.” With currently only 239 cases of coronavirus infections despite sharing an 800-mile-long border with China, this motto has proven effective for Vietnam.

As media outlets around the world have noted, South Korea has had much success in containing COVID-19. South Korea’s news media similarly frames the nation as a leader amidst the global pandemic including coverage of Korea’s assistance to other nations. South Korea’s media has also quoted other nation’s appraisals. In a speech on March First which is a national holiday commemorating Korea’s Independence Movement, President Moon Jae-In announced that the Independence day holiday symbolizes “the spirit of unity for mutual understanding and sympathy,” and that the government will strengthen cooperation with other nations to battle against COVID-19. We also argue that the act of quoting foreign media in displaying the nation’s accomplishments is a way of showing external validation for the Korean government and promoting a patriotic Korean culture.

Coming together on a class project showed us how different countries are thinking about and addressing the COVID-19 crisis and let us see in real time how the media was used in that fight. Just as important, it brought us together and gave us a sense of community. While many other courses inside the university continued on their syllabi for the semester, our class was able to find catharsis in uncertain times by combining our efforts to produce relevant and insightful research.

“I never expected that data scraping would be such a handy tool,” said Lei Zhu MIA ’21. “Working on a class project using data scraping and IBM Watson analysis helped me gain insight into Chinese state media’s messaging strategy in the time of a global pandemic. Though living in isolation, participating in a class project like this gave me a sense of belonging. We are not lost in isolation.”

—Anya Schiffrin with Alexandre Gonçalves and Eve Critton MPA ’20

Eve Critton MPA ’20, Zheying Feng MPA ’20, Yiting Gao MPA ’21, Murilo Nascimento Salviano Gomes, Andrea Greenstein MPA ’20, Breno Lemos Pires, Katie Pearson MIA ’21, Lei Zhu MIA ’21, Kumgyu Sun MPA ’21, Bei Lin Teo MPA ’21, Jueni Tran, Wendy Morphew ’19SPS all contributed to the class research cited above.

We thank others who contributed to the class discussions: Christina Flammia, Hanna Homestead MIA ’20, Isabelle Lee MIA ’20, Murilo Nascimento Salviano Gomes, and Mengtong Wang MPA ’20.